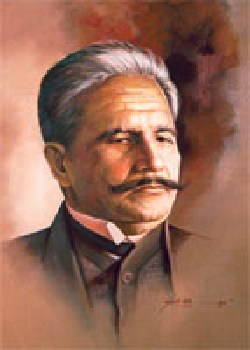

Muhammad Iqbal

Given the current turmoil, which has made it abundantly clear that the people of Pakistan desire a truly representative democratic civilian order, the question above has become very relevant. Essentially – this begs four

questions that ought to be answered to understand the relevance of Allama Iqbal to Pakistan today.

1. What were Iqbal’s views on democracy and how did they fit into the overall Iqbalian-Ijtehadi Islamic thought ?

2. How and why did Iqbal become the national poet and philosopher of Pakistan ?

3. What has been the nature of criticism of Iqbalian thought in Pakistan?

4. What is the future of Iqbalian thought in Pakistan?

1. What were Iqbal’s views on democracy and how did they fit into the overall Iqbalian-Ijtehadi Islamic thought ?

Iqbal famously said something to the effect that democracy merely counts and does not weigh. No doubt this as well as the distinct glorification of Islam (inter alia his concept of the Islamic Superman i.e. Mard-e-Momin and Shaheen) in his poetry has been used by the military rulers of Pakistan.

On the other hand, Iqbal celebrated the coming of democracy or republicanism in his famous couplet:

“Sultan-e-jumhoor ka ata hai zamana”

or “Dawns the era of republican democratic rule”

In his letters to Jinnah – Iqbal declared that “Social Democracy is actually a return to the roots of Islamic history”. He clearly took Syed Ameer Ali’s point of view and considered the state founded by the Holy Prophet an example of republicanism.

So when we say that Iqbal was against democracy, one has to consider what it means.

1. Does it mean Iqbal was against representative rule?

OR

2. Does it mean Iqbal was against something else that goes beyond representative participatory rule?

Iqbal’s conception of a modern Muslim state- which emerges from the Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam is of a state run by representatives elected by the people. In addition to the supreme legislative body, the parliament, including the Non-Muslim members, was also to be the Grand National Ijtehad Council which would meet to modernise Islamic traditions, civil code and criminal code. The reason why his book was denounced unanimously by the Mullahs was because they saw that Iqbal favored giving the state the power to completely change Islam according to modern times. For example he argued that the state could ban polygamy and that would be perfectly Islamic…

Thus it is quite clear – from his lectures atleast- that Iqbal was not against representative rule.

It is also quite clear that he himself used the terms “Social Democracy” and “Spiritual Democracy”, the former being a system of government and society that sought create equitable distribution of power, wealth and participation and the latter a system of religious “movement” which ensured the constant updation of religious tradition.

Infact Iqbal’s famous idea of a “separate Muslim state in North West of India” in 1930 was not inspired by any attempt at achieving group rights or a group-identity consciousness etc but rather the idea that just like Judaeo-Christian ethics have colored the otherwise secular legal systems of the west, Islamic ethics should get a chance to develop and modernise in a similar fashion in a state of its own.

Thus what he was presumably afraid of was the lack of a moral basis for the democratic system. (Ironically similar fears were raised Gandhi in India but Gandhian Religious Moral Philosophy was not allowed any constitutional expression by Dr. Ambedkar). Allama Iqbal favored hyphenated democracy of sorts- a democracy limited by morality determined by Islamic ethics.

While in my view this idea is inherently flawed but it is clear that a majority of Muslims around the world agree with Iqbal’s idea, what they don’t agree with is Iqbal’s liberal interpretation of Islamic law and his readiness to do away with what they consider to be the central motif of islam. The reason why no one mentions Allama Iqbal’s views on democracy because the current pro-Democracy movement is not concerned with the issues that have been mentioned above. The current pro-Democracy movement wants representative civilian rule. Whether this representative rule would be limited by Islamic ethics or human reason is an issue that is irrelevant to the movement.

Issue 2: How and why did Iqbal become the national poet and philosopher of Pakistan ?

Truth be told Iqbal’s stature has been enhanced by the state each passing year. He is no longer just the national poet and philosopher but is now a founding father equal to Mahomed Ali Jinnah in the official state pantheon. How is it that Allama Iqbal- who passed away 2 years before the Pakistan Movement officially kicked off- is held today in equal esteem to Jinnah ?

There is no question that Allama Iqbal was widely respected as the foremost Muslim poet since Hali. But there has been considerable exaggeration when it comes to giving him credit for Pakistan’s creation. According to “Plain Mr. Jinnah” a collection of Jinnah’s personal correspondence, a Muslim League volunteer found Iqbal’s letters to Jinnah in some corner of Jinnah’s legal library in his house in Bombay, after the 1940 resolution. The first edition of Iqbal-Jinnah Correspondence, published by the Muslim League, is from 1941 or 1942.

In my opinion from the period 1947-1958, Iqbal was celebrated as a great poet but not for anything else. It was 1958 onwards that the revision of Iqbal as a founding father began. There are several reasons for it. One major reason is that Army, as an institution, has at best always been uncomfortable with Mahomed Ali Jinnah’s memory. A lawyer-politician and parliamentarian as the founding father and the “Quaid-e-Azam” has always given the army people a bit of a kick in the balls. Ayub in particular , it is said, could never get over Jinnah’s chilly rebuke to army officers (when they complained about British officers) informing them that it was civilians who made policy and not army men. Especially after the threat posed by Fatima Jinnah in 1965, the army realised that Pakistan with a single memory cannot be good for them.

Allama Iqbal in contrast provided a much more workable situation. The Iqbalian concepts of “Mard-e-Momin” and “Shaheen” (even though Iqbal’s Mard-e-Momin and Shaheen could be civilians) were used- much in the same way Nazis used Nietzche’s “Superman”- to invent the “Super-Fauji” who could dodge bullets and travel at the speed of light … all the while managing a pathetic little country like ours.

If Pakistan’s 60 years are mapped in terms of Allama Iqbal promotion, the graph would be highest under Ayub, Zia and Musharraf. The Ulema – including people like Dr. Israr- the same sort Iqbal had warned against- have also had good reason to own Iqbal. Much of Iqbal’s poetry is recited by the Ulema because it speaks of Islamic glory etc.

Issue 3. What has been the nature of criticism of Iqbalian thought in Pakistan?

Allama Iqbal has been criticised by Pakistani intellectuals across the board on several counts, namely:

Liberals/Secularists/Left’s objections

1. Iqbal’s apparently ambivalent attitude towards democracy.

2. Iqbal’s contradictory stances day to day issues confronting Muslims.

3. His championing of “Pidram-Sultan-Bood” or the past glory of Islam.

4. His Mard-e-Momin/Shaheen conceptions lending themselves to patriarchal interpretations including but not limited to the role of military in a Muslim society.

5. His conception of the Muslim majority state in the North West alone…hence Iqbal’s apparent disregard for Bengali Muslims.

6. For writing poetry for the elite and upper classes and not for the masses.

Leading critics of Allama Iqbal include Dr. Mubarak Ali- a leading historian. Another group of intellectuals that seeks to play down Iqbal as a founding father is the Rahmat Ali group which rejects the notion that “Allama Iqbal was the first man to give the idea of Pakistan”. KK Aziz has written extensively on the issue and holds that Allama Iqbal’s scheme was just one of the many schemes to partition India and create an independent North West that emerged starting from 1892 onwards.

Islamists/Theocrats/Right’s objections

The main Islamist objection to Allama Iqbal is that he sought to break the vicious cycle of taqlid and tried to liberate Islam from centuries old intellectual stagnation. This is viewed by the Islamist sections as “Biddah” or innovation. The fear in the minds of the Islamists is that clever rhetoricians would use Iqbal’s logic of Ijtehad to do away with the core principles of Islam. The Islamists accuse Allama Iqbal of attacking Islamic way of life by hinting that the state could if it wanted outlaw polygamy (that he himself was polygamous is another issue) and for endorsing Sir Syed’s view that Interest-banking was not the same as Riba/usury. Allama Iqbal also favored and encouraged people like Allama Pervez and Tolu-e-Islam who took to a more rational interpretation of Islam and this too is not liked by the Ulema.

Issue 4: The Future of Iqbalian Thought in Pakistan

The criticism that Allama Iqbal was ambivalent towards democracy is irrelevant to the future of Iqbalian thought. Pakistanis are- whether some like it or not- completely committed to a civilian democratic system of representative rule in Pakistan based on adult franchise. It is only a matter of time that we have sustainable democracy in Pakistan. Similarly the criticism that he ignored the Bengali Muslims in his conception of a sovereign state is also irrelevant, since Bengali Muslims today have a state of their own.

Similarly the criticism that Allama Iqbal glorified the Islamic Past is usually because of a misunderstanding of Iqbal’s works. Iqbal was terribly conscious of the morass Muslims are stuck in and things have gone from bad to worse since his time.

I for one am sure that both Nietzche and Iqbal would have given up their conceptions of Superman and Mard-e-Momin respectively had they seen the Nazi regime in action with the Superman concept in Germany or the mockery General Zia ul Haq made of the Mard-e-Momin idea.

The major crux of Iqbal’s thought remains relevant even today i.e. to liberate Islam from the shackles of taqlid and re-open the door to Ijtehad. Iqbal imagined Islam not as a stagnant faith but a dynamic life code… which was universal and flexible enough to evolve with time. Just like Sir Syed Ahmed Khan had envisaged Aligarh University as a place for Muslim Ashraf to equip them with modern knowledge, Allama Iqbal’s vision of a sovereign Muslim homeland was to create a place for Muslims to experiment and re-invigorate the deadwood that Islam had become over the centuries and re-discover its dynamism.

The creation of Pakistan itself and the route that was followed shows that Jinnah’s concern was essentially that of a lawyer trying to get his client his fair share in the settlement. The emergence of an independent sovereign Pakistan benefitted and enriched the local and indigenous people who saw an industrialisation that was hitherto denied to them under British rule. The areas that form Pakistan today were essentially hubs of agricultural produce and regions for martial recruitment.

Hence under British rule, this region had remained both politically and economically under-developed. Politically because British ruled Punjab and other provinces of the Pakistan that exists today through the collaboration of the feudal classes and notables. Thus the Commissioner and not an elected representative had his firm control over this region. Economically because this area remained useful for agricultural raw materials and cannon fodder for the Royal Indian Army. It was only Pakistan’s creation that forced the industrialisation of this region. Thus Pakistan itself had an economic and political purpose that has been more or less fulfilled.

Iqbalian thought however has the promise and potential of giving Pakistan a higher purpose: that of unleashing an intellectual renaissance and reformation of the entire Islamic world. Whether it is secular or not, I endorse this idea that the state should become an instrument of reformation and renaissance, but only after guaranteeing that every citizen of Pakistan, regardless of religion, caste, creed or gender has equal rights and opportunities. Only when we’ve put our house in order, we can ponder on this higher purpose.

Al Sunna

October 26, 2009

Thanks for the good info…very good blog site.

ahraza

October 27, 2009

Muslims pride in the belief of the afterlife and respect for our current existence. But now it seems we just don’t give a damn about it all. If I were to tell you that a governor was appointed for paying massive amounts of dollars or a minister is making money by selling LPG (Liquid Petroleum Gas) files, I can guarantee you no less than a thousand emails and text messages would be circulating Pakistan. We are not a nation of drama queens. Enough is enough!

Sameer

October 28, 2009

A secular person who want to create secular country is the one who does not allow his daughter to marry someone not from his religion and if his daughter goes against him, then she will be disowned.

Sameer

October 28, 2009

Equating Zia ul Haq and Nazi era is too far-fetch, is not it? But i guess some people go to any length in order to prove their point even if it is incorrect and irrational

Bin Ismail

February 14, 2010

You’re right. The Zia ul Haq era should be equated to the Halaku Khan era.

Ali

December 1, 2009

@Sameer

Secularism is restrained to the domain of political ideology, and does not deal with person’s ideology. If Quaid-e-Azam adhered to some religious believes, why on earth should it mean that the country-to-come cannot be secular? The founding fathers of USA were puritans (religious), yet should that mean USA cannot be secular?

Ali

December 1, 2009

Very good article – I too wondered, in light of Pre-1947 history, what is going on with Iqbal’s popularity in Pakistan – considering that he was just a poet and an islamic philosopher, having very little to do with the genesis of Pakistan

Nusrat Pasha

January 17, 2010

Essentially belonging to the world of literature, Iqbal commands considerable respect in both Persian and Urdu poetry. He would most certainly have remained uncontroversial if he had not been exalted to sainthood posthumously.

All good poets are philosophers and so was Iqbal. Among the pioneers, Iqbal would positively envy poets like Mir, Ghalib and Dagh. Among the more contemporary ones, we see that inspite of his being state-sponsored, poets like Faiz, Insha and Faraz command, if not more, no less respect.

Along the timeline, Iqbal’s emergence happens to coincide with Pakistan’s drift towards a pro-theocracy path, but this was not a coincidence. He should best be remembered for his rich contributions to literature.

Khullat

February 3, 2010

WHAT IS RELEVANT : Was there any Musawwir-e Pakistan ? Yes, and his name was Jinnah. Was there any Mufakkir-e Pakistan ? Yes, and his name was Jinnah. Was there any Baani-e Pakistan ? Yes, and his name was Jinnah.

CONCLUSION : The very question, whether Iqbal is still relevant, is itself irrelevant. With reference to Pakistan, the one name that has been and will always remain relevant is “Jinnah”.

Bin Ismail

February 5, 2010

Iqbal was a good poet and said well but did nothing exceptional. Quaid-e-Azam may not have been a poet, but read his speeches – he spoke even better and put his noble words into practice.

Khullat

February 5, 2010

@Bin Ismail

I agree as you have rightly suggested, with reference to Jinnah, that we should all ‘read his speeches’.Only then would we be able to compare him with Iqbal. Iqbal said and Jinnah did. It takes a man of action,not poets, to lead a nation.

Bin Ismail

February 6, 2010

Our dear country is going through a very deep crisis. To indulge in shaa’iry and mushaa’ira at this stage would be suicidal. To put it in plain and blunt words, I would say that with respect to the country, Iqbal is and never was relevant. 62 years have been lost in poetry. We need to do some real stuff. Our man is Jinnah, who won us our homeland.

If Jinnah is for a Secular Pakistan, we are all for a Secular Pakistan.

Suv

February 7, 2010

@Bin Ismail

I would say even if Jinnah was not for secular pakistan you should still go for secular pakistan

Salman Latif

February 7, 2010

@Bin Ismail

You just read it – while it’s the usual practice of our liberalist brethern to intentionally cite Jinnah rather than Iqbal, they must know and understand the fact that Jinnah’s struggle had underlying motives for the class he belonged to – namely, the elitist bourgeoisie of his times. And everything after Pakistan’s creation quite testifies to that. In fact, even through the Pakistan movement, you’d barely found many big-wigs without a fine class-background.

Iqbal, on the other hand, was a common man’s man. Even when his poetry is overtly religious at times, taken in all, together with his philosophy, he certainly was the one who’d have lent some intellectual dimension both to the idea of Pakistan and to the state, after Pakistan’s creation. But sadly, the liberalists chose to stick to Jinnah and let go of Iqbal, and the rightist exploiters and army, grabbed this opportunity to frame Iqbal for their own purposes. And consequently, today Iqbal is known as none other but a poet who wrote zealous Islamic poetry. That’s sad indeed!

Bin Ismail

February 7, 2010

@Suv

True,we should go for a Secular Pakistan, in any case,but I have no doubts about the secularist vision of Jinnah.

@Salman Latif

There is a phenomenon called ‘hijacking’. Everything after Pakistan’s creation testifies to one of the most remarkable hijackings of our times. An entire nation founded on the principles of secularism was hijacked in the direction of theocracy.

As far as Iqbal is concerned, he had passed away even before the concept of Pakistan had germinated.So his contributions to Pakistan are about as much as those of Haali who was also a good poet. State-building and nation-building are not religious phenomena.Nobody let go of Iqbal.We all recognize his literary status.

Salman Latif

February 7, 2010

I am not trying to show how Iqbal contributed to the concept of Pakistan or if he did at all. My point is: his poetry was a fine trigger towards social activism among Muslims.

And in a post-Pakistan era, his concepts regarding Islam are very much relevant since while it sounds good to say that Pakistan was founded upon secular grounds and that be truth, although I have reservation upon that too, the fact remains that we have a Muslim majority population where an average Muslim is entirely thwarted off the intellectual discourse by the regular Mullah. Iqbal’s notion of reconstruction of religious thought can be a starting point towards establishing a premise to start intellectual discourse among this populace of Muslims.

Bin Ismail

February 7, 2010

@Salman Latif

I don’t think it would be a very good idea to turn to poets for either reconstruction of religious thought or for nation-building. Poets and philosophers should be allowed to flourish in their own sweet dreams.

Salman Latif

February 7, 2010

That’s a very careless statement 🙂

Bin Ismail

February 8, 2010

@Salman Latif

When you take into account the fact that our nation is already afflicted with enough illusions and delusions, and when you take into account the fact that most of us tend to live in a state of denial and shy out from aknowledging the most glaring of realities, and also when you take into account the fact that reconstruction of religious thought and intellectual discourse is more a fruit of broad-spectrum education than a single poet’s poetry, then I sincerely believe you will find my statement calculated rather than careless.

Salman Latif

February 8, 2010

When you take into account the overt religious undertones of our society, the religious fervor of a majority which really is a glaring reality, only unavailable to a deluded few, and when we see that while our youth, in its desperation, clings to all sorts of manipulated versions of religion and faith and hence the popularity of the likes of Zaid Hamid, then let me say that Iqbal is very relevant in today’s days and what you are trying to propose is rather a very impractical way of addressing the issue where you intend to let everything be and concentrate on any particular facet, say education and then go on to hope that can even change things! Oh and mind you, education alone would barely do any good – it’s the renaissance of the intellectual discourse itself that renders that education useful – or it becomes just another tool to manipulate with!

Bin Ismail

February 9, 2010

You’ve inadvertently defeated your own,otherwise eloquently presented argument, by mentioning the influence of ‘the likes of Zaid Hamid’. You see, Zaid Hamid and his likes rely on Iqbal and abundantly quote him.So yes indeed, Iqbal is relevant today, but only to gentlemen like Zaid Hamid and Aamir Liaqat.

When a nation confronts a real crisis,it has to learn to do away with emotionalism and sloganism and tread its path with more calculated steps. Renaissance of intellectual discourse is not brought about by poets.Renaissance always follows rationality and poetic romanticism is a distraction from rationality.With both feet on the ground, this nation will have to exercise introspection, realize its errors and rationally correct them.

Salman Latif

February 9, 2010

Rather, my argument that the likes of Zaid Hamid are influential today and your admission of the fact directly bears upon the crux of your debate since it clearl establishes the facts that Iqbal, in the wrong hands,could well be used by such culprits as a name to gather masses, especially youth, since his name still carries a grand infuence on those masses.

The second flaw in your cited argument is: Iqbal was not just a poet. That’s precisely why I presented him as a prospective starting point for an intellectual renaissance. But then again, since the secularists find it difficult to pick him and study him and simply wish to live on the dream of irrelevance, he continues to be exploited by Zaid Hamid.

However, even if we consider your argument in it’s incompleteness, I believe literature has a grand influence on the mind of an average man and it’s not without reason that your find those fundos out there being brainwashed through certain literatueres. So, even a poet then, and that too of a strong influence on our masses, ought not be neglected especially when he was among the very few intellectuals of the sub-continent in our immediate pre-partition era.

Bin Ismail

February 9, 2010

@Salman Latif

Your concern about ‘Iqbal in the wrong hands’ is understandable.The solution you appear to be proposing is that Iqbal be taken up by the right hands.An alternative solution could be to change the hands.Even the Quran in the wrong hands,is bound to be misused,let alone Iqbal.The hands,therefore, need to be changed.

Now coming to Iqbal,if the pivotal issue is having a poet around,then why Iqbal.Among the ‘asaataza’ Ghalib certainly ranks higher.Among the Pakistani poets Faiz enjoys greater appeal.Our real problem is that we are prone to mixing everything and anything irrelevant with ‘the business of the state’.When it’s not religion,it’s poetry.

The renaissance, you so keenly look forward to, has to be preceded by dispassionate rationality.

Khullat

February 9, 2010

@Bin Ismail

You’re right. These “wrong hands” have to be replaced – hands that seek to play with Islam for their political motives – yes these hands have to be replaced. Enough wrong has been done to our dear country in the name of religion – and enough is enough.

Salman Latif

February 10, 2010

@Bin Ismail

Well…there you agree with me that the hands that are currently trying to ‘own’ Iqbal need be changed – and hence, Iqbal needs to be treated by the right hands, or shall I say right minds i.e. the intelligentsia.

As for ther other poets you mentioned, well…I sure have no problem with that. In fact, Jalib and Faiz’s poetry was indeed much lauded because they used it as a tool to criticize suppression and dictatorships in the country and to cite their sentiments over social phenomenon.

Now if you deem all that hogwash and not at all useful in the intellectual growth of the society, and if you’re telling me that we need something ‘practical’ well then…on that literalist approach, let’s abandon our blogs and go out there and do something – surely, our nation needs ‘practical, dispassionate rationality’ and ‘more than mere words’ and that, going by your logic, quite render this blog too a useless space to voice your opinion at. 😉

Bin Ismail

February 10, 2010

@Salman Latif

May I respectfully conclude that we agree on the need for change of hands and minds. On a personal level, I continue to believe that Religion has to be detached from State and State has to be detached from Religion. Otherwise Religion will remain susceptible to the wrong hands and minds. I wholeheartedly respect your opinion about Iqbal, but I hold my conviction that with reference to this state and nation, if there is one name that emerges as truly relevant, it is “Jinnah”.

I assure you it was a pleasure communicating with you.

Salman Latif

February 10, 2010

I have similar sentiments over the discussion with you. 🙂

Usman

February 17, 2010

why then partition? India today is a great democracy! now dont say no, no its not…look at the separatist states, the slums etc…they are a democracy…their president was a muslim…they have chrisitian representatives…they are an equal opportunity employer! why then Jinnah sought for a separate state for Muslims? why not just a separate state? if its just a separate state then it concludes he wished to govern a state…a pure political desire!

now being living in a so called democracy let us let everyone practice their freedom of speech. if everyone 1 out of 10 educated people carry an ideology and feel it to be the absolute and leave no room for the acceptance of authenticity of another then either there is going to be a war or their are more Pakistans. now this seems skeptical but if you look around everyplace you sit, you’ll find people with complete systems for the country. yet they do not vote for a somewhat conforming candidate with some hope and they themselves can do nothing other than talking and posting taboos online and accumulation peace of mind by “bravo! nice article” etc. be famous or refer to some philosophy!

Nusrat Pasha

February 18, 2010

@Usman

You may find it useful to go through the article at :

As late as November 14, 1946, which means merely 9 months prior to independence, Jinnah said, “….I am NOT fighting for Muslims, believe me, when I demand Pakistan.” This clearly answers your question ‘why then partition?’. Jinnah pursued Pakistan neither in the name of Islam, nor exclusively for Muslims. You see, Quaid-e-Azam was more than willing to endorse an undivided India, which he openly did when he accepted the Cabinet Mission Plan. The Congress leadership, not Jinnah wriggled out of this last chance of keeping India undivided. All that Quaid-e-Azam wanted was to ensure that the social and economic interests of the conglomerate of the Muslim-majority states remained secure. This was an assurance that Gandhi, Nehru and Patel were not willing to extend. The weaker and smaller conglomerate of the Muslim-majority states was at risk of being economically subdued by the larger and more prosperous conglomerate of the Hindu-majority states. So, Pakistan was created neither in the name of Islam, nor exclusively for Muslims, but rather in pursuance of a secure economic future for the Muslim-majority states of the Subcontinent. By any standards, Jinnah was perfectly right – morally, legally and politically right – in doing so.

rana inam

May 31, 2010

iqbal is grate.

aiman adnan

July 28, 2011

can u plz write some speeches of allama iqbal related to state and society.

Mohsin

October 14, 2012

You go too far and your writing clearly depicts how good a nationalist, patriot and even a secular you might be. Iqbal has always been one of the founding fathers of this country and not just some poet elevated to gain personal interests by any body or institution of pakistan. The very start of your writing made me feel nauseated. Write fair, judge fairer. Please stop poisoning the thoughts of people turning to internet for education. Keep your filthy ideas to yourself.

Tehreem

October 26, 2013

stop poisoning the mind of our nation by ruining our history! neither iqbal was secular nor was Quaid-e-azam! Both of them were were against theocracy but didn’t favoured western democracy as a whole! They, by no way were away from Islam and were in favour of Islamic democracy! If u ppl mean ”equality of all citizens before law and protection of minorities” is secularism then i must say that Islam is itself secular! n if secularism means ”adopting western culture, non enforcement of Islamic laws, allowing non-muslim to be the head of the state etc etc” then u are truly mistaken in the idea that Quaid n Iqbal wanted the latter type of secularism bcoz it buries the concept of 2-nation theory!

mohammed asif ali

January 17, 2014

Great Collection Of Urdu And English Shayaris And Quotes. Latest Shayari And Poetry Collection Of Dr. Iqbal Sahab. beautiful quotes by dr. iqbal sahab

papu

September 1, 2014

Iqbal was a Satanist read his inspiration from Nietzieh

papu

September 1, 2014

our governments have fooled people of believing in Jinnah and Iqbal they were agents of illuminati now NWO search the net research wisely you will find it

papu

September 1, 2014

Jinnah and Iqbal were inspired by Liberalism in the west Iqbal fooled the Indian Muslim nation through poetry as Nietzieh misleaded his people

you can find evidence from various sources as well

papu

September 1, 2014

please read these linkshttp://sites.google.com/site/911newworldorderfiles/sc0126bb07.jpg

papu

September 1, 2014

I hope now you wouldnt recall Jinnah as QA and Iqbal as DR Allama

thanks

papu

September 1, 2014

please also note in the making of Pakistan jinnah and iqbal played an instrumental role by the western elite to divert the real objective of making of Pakistan.

the real factors for Pakistans creation were consealed by our educationists policy makers and intelligentia on the instructions of the west and dumming us now through media and new induced political scenerios inside Pakistan.

முஹம்மது குட்டி

September 15, 2014

Papu yar tung na ker …..i,m really sure you are a ………

papu

December 4, 2014

But my heart bleeds for the poor people of Palestine , who trusted the No 1 Muslim poet ( as tom tommed by Rothschild media ) of the planet , not to let them down.

Here was a Muslim who kept giving unsolicited proof that his forefathers were Sapru clan , Kashmiri Pandit Brahmins. But what I do not understand is why his father Shaikh Noor Mohammad was a poor illiterate tailor.

Iqbal was taken to Germany by Rothschild to introduce him to the “two nation theory ” for divide and rule.

Till he was unleashed back into India from Germany, by German Jew Rothschild , totally brainwashed by a Jewish honey trap –a gorgeous German girl by the name of Emma Wegenast, Indians lived in harmony as Muslims and Hindus –with a common enemy, the British.

During the 1857 freedom war, Hindus and Muslims –all Indians– fought shoulder to shoulder against the foreign white invader , the British. British East India Company was owned by German Jew Rothschild, who gre opium in India and sold it in China.

Iqbal is highly respected in Pakistan. In fact he is No 1 citizen of Pakistan, even ahead of Jinnah.

At Heidelberg Germany, one street ( at Marriott Hotel over looking river Neckar ) is named after Iqbal called IQBAL UFER.

Why not?

Rothschild rewarded him for his role in pouring cold water over Muslim world anger over Palestine and ending the powerful Ottoman empire at Turkey.

Today Rothschild holds Bilderberg conference at Istanbul and the Turkish army and economy/ banks are controlled by the Jews.

Iqbal was first noticed by Rothschild , as a piece of clay to be moulded, when he wrote something which surprised everybody.

Mind you, at this time the freedom movement was in full swing in India, especially in the area where he lived.

Upon the death of Queen Victoria in 1901, Dr. Iqbal penned an epicedium of ten pages, entitled “Tears of Blood “.

The Queen died on the day of Eid-ul-Fitr, and Iqbal the slave wrote :

“Happiness came, but grief came along with it,

Yesterday was Eid, but today muharram

(Month of the year associated with the deepest mourning

for Muslims) came.

“Easier than the grief and mourning of this day,

Would be the coming of the morn of the day of judgment.

“Ah! the Queen of the realm of the heart has passed away,

My scarred heart has become a house of mourning.

“O India, thy lover has passed away,

She who sighed at thy troubles has passed away.

“O India, the protective shadow of God has

been lifted from above you,

She who sympathised with your inhabitants has gone.

“Victoria is not dead as her good name remains,

this is the life to whomever God gives it.

“May the deceased receive abundant heavenly

reward, and may we show goodly patience.”

(Baqiyyat-i Iqbal, Poem runs over pages 71– 90.)

papu

December 4, 2014

In 1905, Iqbal was a lecturer at the Government College, Lahore . He was invited by a student Lala Har Dayal to preside over a function. Instead of delivering a speech, 27 year old Iqbal sang Saare Jahan Se Achcha.

The song, in addition to embodying yearning and attachment to the land of Hindustan, expressed “cultural memory” and had an elegiac quality. This poem shows his mindset—his love for his motherland Hindustan where he saw everything through a secular broad prism.

This lovely poem stirred the imagination of Indians and the Muslim world. His reach to the Muslim world would be like a 1000 newspapers .

Then hey-presto—he was whisked away by Rothschild to England and Germany, where he would be tutored and brainwashed for three years . While in England , Rothschild made sure that he was inducted into the executive committee of the Muslim League’s British chapter in 1908. He was instrumental in drafting the constitution of Muslim League.

He would later divide the Hindus and Muslims of India, he would put the last nail in the coffin of the Ottoman Caliph at Istanbul and he would keep the Muslim opinion for the people of Palestine in reign.

This is the meaning of being a DOUBLE AGENT, gentlemen. What do you know of the world of double agent deceit?

Mahatma Gandhi was one.

Punch into Google search:–

MAHATMA GANDHI, RE-WRITING INDIAN HISTORY- VADAKAYIL

and

THE DIABOLICAL BRAINWASHING OF GANDHI- VADAKAYIL

In December 1911, on the occasion of the coronation of King George V, Iqbal wrote and read out a poem entitled `Our King’:

“It is the height of our good fortune,

That our King is crowned today.

“By his life our peoples have honour,

By his name our respect is established.

“With him have the Indians made a bond of loyalty,

On the dust of his footsteps are our hearts sacrifced.”

(Baqiyyat-i Iqbal, p. 206.)

papu

December 4, 2014

Then came the Rowlatt act , which both Hindus and Muslims opposed tooth and nail. The Muslims were more angry with the British those days and Christians snatched away Hindustan from the Muslims—NOT the Hindus.

Even Gandhi was unable to keep things smooth for the British.

Drafted by a British judge Sir Sidney Rowlatt, this act effectively authorized the British government to imprison for a maximum period of two years, without trial, any person suspected of terrorism living in the Raj and gave British imperial authorities power to deal with revolutionary activities. The unpopular legislation provided for stricter control of the press, arrests without warrant, indefinite detention without trial, and juryless in camera trials for proscribed political acts. The accused was denied the right to know the accusers and the evidence used in the trial.

The Rowlatt Act came into effect in March 1919. In the Punjab the protest movement was very strong, and on April 10, two outstanding leaders of the congress, Dr. Satya Pal and Dr. Saifuddin Kitchlew, were arrested and taken to an unknown place ( they imprisoned them secretly in Dharamsala ) . A protest was held in Amritsar, which led to the infamous Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919.

When all these violent protests against the impending Rowlatt act was going on what does Rothschild stooge Iqbal do?

At the request of criminal Sir Michael O’Dwyer, governor of the Punjab, Iqbal chose to eulogize the empire in the wake of the infamous Rowlatt Act. In it, addressing the King of England, Iqbal says:

“If there is freedom of speech and writing here, if there is peace between the Temple and the Mosque here,

“If there is an organised system of business of the various peoples here, if there is strength in the dagger and life in the sword here,

“Whatever there is, it has been granted by you, O honoured one, this land is alive only because of your existence.

“I am the tree of loyalty, love is my fruit, a just witness to this statement are my actions.

“Sincerity is selfless, so is truth selfless, so is service, and so is devotion selfless,

“Pledge, loyalty and love are also selfless, and devotion to the royal throne is also selfless,

“But being human the thought which arises naturally is, that your favours are manifest upon India.”

This was published in the paper Akhbar-i Haq, the magazine Zamana of Kanpur, and the book Hindustan aur Jang ‘Alamgir (`India and the World War’) by L. Ralya Ram. It was then published in Baqiyyat-i Iqbal, on pages 216 to 219. It was first read out by Dr. Iqbal himself at the Punjab University Hall, Lahore.

papu

December 4, 2014

USSR had a lot of Muslim areas . Iqbal kept the Muslims ( who looked to him for spiritual guidance ) under control during the Bolshevik revolution, against the Russian Czar. How many of you know that Karl Marx was of Rothschild German Jew blood?

How many of you know that Trotsky, Lenin , Stalin , Gorbachev, Yeltsin etc were Jews controlled by Rothschild ?

Even today many leftists and Communists claim Iqbal’s legacy, particularly citing masterpieces like ‘Karl Marx Ki Awaz’, ‘Bolshevik Roos’, ‘Saqi Nama’,‘Lenin Khuda Ke Huzoor Maen’, ‘Saqi Nama’, ‘Iblees Ki Majlis-e-Shoora’, ‘Sarmaya o Mehnat’ etc.

An Indian communist Shamsuddin Hasan declared “ Even a half-wit can see by reading his works Khizr-i-Rah (The Journey’s Guide) and Payam-i-Mashriq (The Message of the East), that Allamah Iqbal is not only a communist– but communism’s high priest”.

A harried Iqbal who never expected intelligent critics , made a pathetic defence the very next day in the daily Zamindar as follows:

“I am a Muslim and believe, on the basis of logical reasoning, that the Holy Qur’an has offered the best cure for the economic maladies of human societies. No doubt the power of capitalism is a curse if it exceeds the limits of the happy mean. But its complete elimination is not the right way for freeing the world from its evils as the Bolsheviks propose. Russian Bolshevism is a strong reaction against the selfish and short-sighted capitalism of Europe. But in fact the European capitalism and the Russian Bolshevism are two extremes. The happy middle path is what the Holy Qur’an has shown to us and to which I have alluded above. The equitable Shariah aims at protecting one class from the economic domination of the other, and in my belief, the path chosen by the Holy Prophet (P.B.U.H.) is the one best suited for this purpose.”

It was a bit too late for lame excuses.

papu

December 4, 2014

In the following verse Iqbal calls Rothschild’s blood relative Karl Marx a Prophet (sic!) :

وہ کلیم بے تجلی وہ مسیح بے صلیب

نیست پیغمبر و لیکن در یغل دارد کت []

He a Moses without divine manifestation; he a Christ without a Cross? And though not a Prophet or Messenger of God but has got a Book in his bosom).

Now check out what Iqbal has to say about Jew Lenin.

In Baal-e-Jibreel (Gabriel’s Wing), Allama Iqbal, the Muslim , describes the encounter of the Lenin with God. The discussion that went on between Lenin, God, and the angels during their meeting is spread over three poems.

In the first poem, “Lenin before God”, Lenin acknowledges the presence of God in the “nature’s infinite music”. With remarkable honesty, Lenin proceeds to describe the situation on Earth to God. Here, instead of flattering the Deity, Lenin files his complaint:

Omnipotent, righteous, Thou; but bitter the hours,

Bitter the labourer’s chained hours in Thy world!

When shall this galley of gold’s dominion founder?

Thy world Thy day of wrath, Lord, stands and waits.

After hearing the fiery address of Lenin, the angles also express their support for the Lenin’s arguments in “Song of the Angles”, and request the God to bestow another glance to the earth:

Reason is unbridled yet,

Love is still a dream;

Thy work remains unfinished still,

O Craftsman of Eternity!

In the concluding part of the sequel, “God’s Command to his Angles”, the Lord, convinced and moved by the contentions of Lenin, orders the angels to provoke a revolution on Earth:

Rise, and from their slumber wake the poor ones of My world

Shake the walis and windows of the mansions of the great!

Kindle with the fire of faith the slow blood of the slaves

Make the fearful sparrow bold to meet the falcon’s hate!

Close the hour approaches of the kingdom of the poor—

Every imprint of the past find and annihilate!

Find the field whose harvest is no peasant’s daily bread—

Garner in the furnace every ripening ear of wheat!

Banish from the house of God the mumbling priest whose prayers

Like a veil creation from Creator separate!

God by mm’s prostrations, by man’s vows are idols cheated-.

Quench at once in My shrine and their fane the sacred light!

Rear for me another temple, build its walls with mud—

Wearied of their columned marbles, sickened is My sight!

All their fine new world a workshop filled with brittle glass-

Go! My poet of the East to madness dedicate.

86Jeffery

August 27, 2017

I see you don’t monetize your website, don’t waste your traffic, you can earn additional bucks every month because you’ve got hi quality content.

If you want to know how to make extra $$$, search for: best adsense alternative Wrastain’s tools